Summary of 2003 Excavations at the Kendall-Gardner Site

Department of Archaeological Research

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Williamsburg, Virginia

2010

Summary of 2003 Excavations at the Kendall-Gardner Site

Introduction

During the summer of 2003 the Department of Archaeological Research, with assistance from students from the College of William and Mary, excavated an 18th-century sawpit just west of the George Wythe property, north of the Bruton Parish Churchyard. Though vacant today, Colonial Lot 241 was occupied successively, during the late 1760s and early 1770s, by two carpenters, Joshua Kendall and James Gardner. Advertisements printed in the Virginia Gazette provide accounts of the types of work that Kendall and Gardner performed-everything from painting and gilding to sash-making and plumbing. Yet, the appearance of this carpenter's yard remains sketchy. The purpose of the 2003 excavation was to gather physical evidence for the Kendall-Gardner trade site, enabling Colonial Williamsburg to reconstruct an historically-accurate carpenter's yard sometime in the future.

Project Background

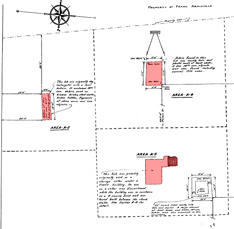

The sawpit on which the 2003 excavation focused was first noted in 1938. In that year the Wythe property was explored through "cross-trenching," the then-current method of locating buried brick foundations by digging closely-spaced shovel trenches. James Knight, the architectural draftsman in charge of the project, recorded three significant features on the portion of that lot once occupied by Kendall and Gardner. The first was a large rectangular pit measuring 13 feet long, 4 feet wide, and 6 feet deep; the fill of this pit was dug out in order to measure and record its dimensions. The two remaining features appeared to be the robbed cellar holes of two structures. Again, these were excavated for recording purposes. No interpretation was offered for these features, nor were they incorporated into the 1940 reconstruction of the Wythe property, though it was believed at the time that all three had something to do with the George Wythe household.

In 1958, new documentary research uncovered the fact that George Wythe had actually never owned Colonial Lot 241. When, though additional probing, Kendall and Gardner emerged as tenants on this rental property, Colonial Williamsburg carpenters requested an archaeological reexamination of the three features to determine whether they represented elements of a carpenter's yard. The resulting project,

2

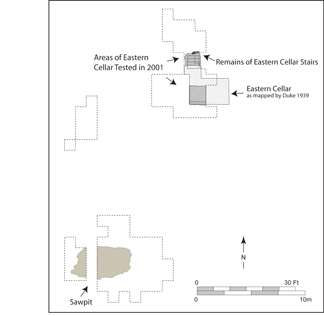

undertaken in 2001, accomplished the excavation of approximately two-thirds of what we now feel confident is a sawpit, and sampled the fill of the eastern of the two robbed cellars. This partial excavation produced an astounding number of artifacts, and when the project ended in December 2001, it was due not only to the approaching winter, but to a lack of funding with which to proceed responsibly on so rich an archaeological site.

undertaken in 2001, accomplished the excavation of approximately two-thirds of what we now feel confident is a sawpit, and sampled the fill of the eastern of the two robbed cellars. This partial excavation produced an astounding number of artifacts, and when the project ended in December 2001, it was due not only to the approaching winter, but to a lack of funding with which to proceed responsibly on so rich an archaeological site.

Kendall-Gardner Excavation 2003

In 2003 renewed funding permitted archaeologists to return to the Kendall-Gardner site with two goals. The first was to complete excavation of the sawpit in order to record final dimensions, examine the sawpit for evidence of a wooden or brick lining, and to recover artifacts that might define the types of activities taking place on the site. A second, and more pressing, objective of the 2003 excavation was to find evidence of a structure protecting the sawpit from the elements. (After two summers of excavation, the second of which was very rainy, it became clear to a soggy

3

excavation crew that an uncovered sawpit in this location would have been useless due to frequent flooding.)

excavation crew that an uncovered sawpit in this location would have been useless due to frequent flooding.)

Between May and early August 2003, field school students excavated the remaining third of the sawpit fill. Although archaeologists were aware that this fill had been excavated in 1938 and thrown back into the pit once its dimensions had been recorded, they remained hopeful that earlier crews had left pockets of fill to be examined first-hand. Sadly, this was not the case. Measurements taken near the bottom of the sawpit revealed dimensions nearly identical to those recorded in 1938, indicating that both groups of excavators observed the same boundaries. Measurements at the top of the sawpit, however, were considerably larger than those recorded in 1938 (15½ feet long by 8¼ feet wide, versus 13 feet long and 4 feet wide as recorded in 1938). Evidently Knight's crew left this feature open for a considerable amount of time, during which the sides eroded significantly.

Careful examination of the pit sides near the bottom, where the edges were more intact, revealed no evidence of a wooden or brick lining, suggesting that the Kendall-Gardner sawpit was relatively crude.

Though frustratingly jumbled by virtue of having been excavated in 1938, the artifacts contained in the sawpit fill still revealed much about the site's long and varied history. Pieces of dressed stone found in the pit are likely to have originated in Bruton Parish church, and were probably deposited on the site before 1750, when construction of a church wall physically separated these contiguous properties. A significant assemblage of colonoware, a locally-made earthenware thought to be used and/or produced by slaves, suggests an African-American presence on this site or nearby. Other artifacts can be tied with some certainty to Kendall or Gardner: pieces of a pit-saw blade and a number of pieces of worked and un-worked lead.

4Evidence of later occupation is equally intriguing. French gun flints, wig curlers, regimental buttons, and a collection of French wine bottles are traceable to a detachment of the Bourbonnais Regiment encamped on this property during the winter of 1781-82. Additionally, the sawpit yielded a surprising number of coins, which may have been the product of Richard Collins, tenant on Lot 241 from 1777 to 1779. Colonial Williamsburg carpenter Noel Poirier has recently uncovered an account written by Henry Hamilton in which Hamilton describes his 1779 imprisonment in Williamsburg, and the fact that he shared a cell with a "Mr. Collins," who was held for counterfeiting.

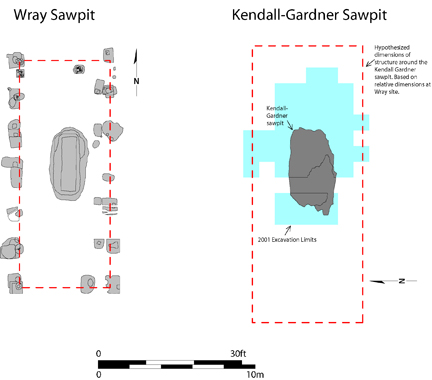

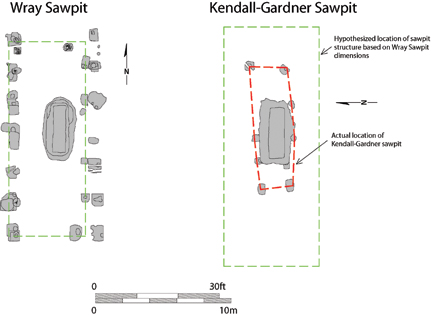

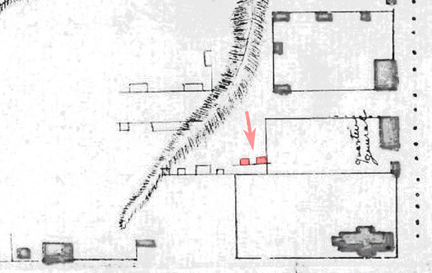

In addition to completing excavation of the Kendall-Gardner sawpit, archaeologists successfully identified the structure that covered it. Sawpits are uncommon archaeological features in the Historic Area. In fact, the only other known example is the James Wray sawpit, identified in 2002 just two blocks to the west of the Kendall-Gardner property. The Wray sawpit was covered by a post-supported structure, measuring approximately 50 feet long and 30 feet wide, which was found archaeologically by regularly-spaced post impressions in the ground. Not only did this fortuitous discovery provide an example of what the Kendall-Gardner structure might look like, it also, through the use of scaled drawings, allowed archaeologists to predict where they might find posthole evidence in relation to the pit.

The 2003 excavation proved that, despite similar sizes of the two pits themselves, the structure protecting the Kendall-Gardner sawpit was significantly smaller and less imposing than that at

5

Wray. The Kendall-Gardner structure measured approximately 30 feet long by 8 feet wide, and was represented by nine postholes, four on the north side of the pit and five on the south side. Substantial erosion around the top of the pit may explain the uneven number of supports. The odd angle at which the Kendall-Gardner structure was set certainly suggests that it was a purely functional construction, thrown up without tremendous regard for aesthetic concerns.

5

Wray. The Kendall-Gardner structure measured approximately 30 feet long by 8 feet wide, and was represented by nine postholes, four on the north side of the pit and five on the south side. Substantial erosion around the top of the pit may explain the uneven number of supports. The odd angle at which the Kendall-Gardner structure was set certainly suggests that it was a purely functional construction, thrown up without tremendous regard for aesthetic concerns.

While identifying the sawpit structure was fairly straightforward, assigning a date of construction has been less so. Archaeologists generally depend on artifacts found in postholes to provide construction dates for post-supported buildings. In the Kendall-Garner case, however, the four postholes excavated (those at the northeast, northwest, southeast and southwest corners) yielded no artifacts whatsoever. Postholes with no artifacts are generally attributable to early occupations, those taking place before an accumulation of surface debris made it difficult to backfill a hole without incorporating healthy amounts of trash. Kendall's 1769 rental of the property seems very late in Williamsburg's history for a "first occupation," no matter how marginal the lot. Thus, dating for the sawpit remains an important question, although the fact that two carpenters appear to have occupied the lot, one after the other, in the early 1770s (and no other known occupants seem to

6

have any need for a sawpit) narrows the likely dating considerably. Still, archaeologists are more comfortable with independent evidence.

6

have any need for a sawpit) narrows the likely dating considerably. Still, archaeologists are more comfortable with independent evidence.

Future of the Kendall-Gardner Site

The 2003 Kendall Gardner excavation accomplished the primary goals of (1) defining the authentic site of a sawpit that can be used in active interpretation of a carpenter's yard, and (2) establishing the footprint of the structure surrounding the pit. With these two interpretive pieces in place, Colonial Williamsburg carpenters may begin to reconstruct and interpret pit-sawing confident that this portion of the site can be made to look pretty much as it did during Kendall and Gardner's tenures.

There appear to be additional components of the Kendall-Gardner complex that have not yet been investigated, and may be added to a reconstructed site in the future. Among the most promising are the two cellars identified in 1938, and probed again in 2001. These two structures appear on the Frenchman's Map of 1781, and therefore presumably were standing at approximately the time of Kendall and Gardner's occupation. It is not a stretch to imagine them as shops, or even the "lead manufactory" described in the Virginia Gazette as associated with Joshua Kendall and his business partner, Joseph Kidd. Unfortunately, the cellars were excavated pretty fully in 1938, and re-excavation of the fill will not provide definitive proof of their function (after all, we don't necessarily know where on the property the backfill originally came from, and just finding carpentry-related material in one or both of the cellars does not mean that it originated there). This is a fundamental problem with having to re-excavate formerly-cross-trenched foundations in the search for specific clues to what archaeologists term "activity areas."

However, excavation between the sawpit and these cellars (in the areas between the 1938 cross-trenches) may produce evidence of connected work spaces, strengthening the association with Kendall and Gardner. Near the end of the 2003 season, archaeologists began uncovering an area of brick rubble that may have potential in this regard. This layer of rubble begins near the northeast corner of the sawpit, and extends northward toward the eastern cellar. Though only a small portion of this layer has been uncovered, our hope is that future excavations will prove it to be a work surface extending between the sawpit and cellar. Should this be the case, and if carpentry-related artifacts and debris are found in and on top of this surface, we can make a good case that one or both of the cellars were used (and perhaps lived in) by Kendall and/or Gardner.

An additional advantage to excavating undisturbed areas between the sawpit and the cellars is that artifacts from those layers, never excavated previously, can be compared with material from the sawpit fill. If match or mends are found, we presume that the sawpit material originated in this area, or at least on this site (a fairly fundamental assumption that we have made, but not proved to this point).

The 2003 Kendall-Gardner excavation has been both productive and encouraging. This site has proven to be a very rich resource, and holds great potential as one of the Historic Area's very few authentically-reconstructed work yards showing the carpenter's trade. Like many other craftsmen, carpenters often occupied a relatively low rung on the economic scale, unable to build fancy homes that are found elsewhere in the Historic Area. They appear to have often rented a

7

lot or lots, constructing relatively ephemeral work sites behind or near their temporary homes. While presumably obvious to the casual 18th-century visitor or town resident, these work yards are hard to find and define archaeologically, and the absence of large brick foundations meant that they were not often reconstructed when Williamsburg was first rebuilt. Archaeologists have known that these types of sites were seriously underrepresented in Williamsburg; it is only relatively recently that we have figured out ways to bring authenticity and vibrancy to the "townscape" by using careful archaeological excavation to find and interpret these shadowy remains. Difficult as they are to accurately identify, it is this type of site that holds some of the greatest promise for more accurately reconstructing what life was really like in 18th-century Williamsburg.

lot or lots, constructing relatively ephemeral work sites behind or near their temporary homes. While presumably obvious to the casual 18th-century visitor or town resident, these work yards are hard to find and define archaeologically, and the absence of large brick foundations meant that they were not often reconstructed when Williamsburg was first rebuilt. Archaeologists have known that these types of sites were seriously underrepresented in Williamsburg; it is only relatively recently that we have figured out ways to bring authenticity and vibrancy to the "townscape" by using careful archaeological excavation to find and interpret these shadowy remains. Difficult as they are to accurately identify, it is this type of site that holds some of the greatest promise for more accurately reconstructing what life was really like in 18th-century Williamsburg.

- Meredith Poole

November 2003